Lightning over the ocean

A bomb without forgiveness

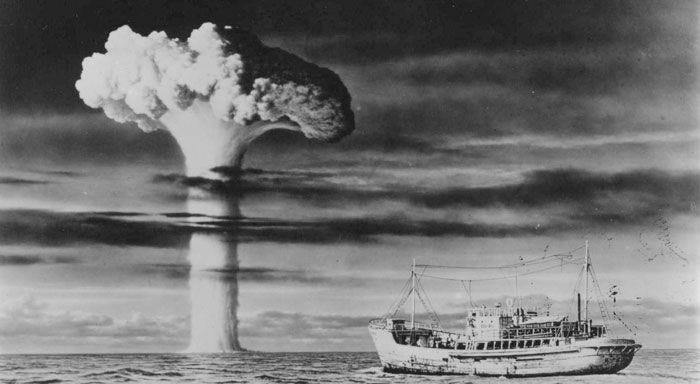

At dawn on March 1, 1954, in the blue immensity of the Pacific, the Daigo Fukuryū Maru, a small fishing boat of just over 30 meters, floated silently off Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands archipelago. On board, twenty-three Japanese fishermen were preparing for another day's work, unaware that they were in the midst of a military experiment that would shake the entire world.

In the silence interrupted only by the sound of the waves and the jingling of the anchor chain, Aikichi Kuboyama, the ship's marcher, slowly sipped a cup of tea while in the radio compartment he checked the short waves for interference. He was a man of few words, in his fifties, with a calm look of someone who has lived through many experiences, but that morning there was something strange in the air. A surreal silence, a heavy atmosphere.

Then, suddenly, it happened.

At 06:45 local time, a flash ripped through the sky to the west, clear, blinding, unnatural. A burst of yellowish-white light turned morning into day, then into a fiery orange sphere, rising into the sky like a slow apocalypse.

“Is it lightning?” murmured one of the sailors. “No--a Pika-don?” ventured another, calling to mind the still vivid memory of Hiroshima.

A few minutes later, a double shock wave hit the ship like a dull fist. The sea shook. Dishes flew, fishing rods bent. Fishing lines, still taut under the surface, swayed like snakes. Some fell. Others remained motionless, their eyes glued to the glow that was slowly fading into the clouds. Kuboyama made a quick mental calculation: seven minutes between the light and the shockwave.

The distance had to be at least 130-140 kilometers. He found a point on the nautical chart: the Bikini Atoll.

That morning, fishing had begun like so many others, but their ship was about to become the symbol of a new threat: nuclear war, which was already burning, even without there being any real combat.

Chronicle before the explosion

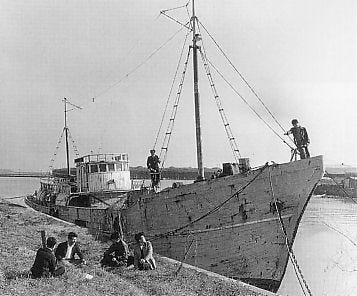

The Daigo Fukuryū Maru, also known as the “Lucky Dragon No. 5,” was hardly an imposing ship. It was a wooden fishing vessel designed for ocean fishing for tuna. It was part of the fleet of Yaizu, a small Japanese town on the southern coast famous for its seafaring tradition.

The crew consisted of twenty-three men, many of whom had families waiting for them in port, and the voyage was planned to last several weeks. On board was Aikichi Kuboyama, the marcher, one of the most experienced and respected members. He was a former military radio operator during the war and knew the waves, routes, and peculiarities of the ocean inside out. He was seen as a solid, almost fatherly figure to the young sailors.

When they set sail from Yaizu Harbor on January 22, 1954, everyone thought their destination was south to the Solomon Islands. It was a safe, well-known route. But during the voyage, Misaki, the fishing boss, and shipowner Nishikawa decided to change direction: they wanted to head for the Midway, where tuna were said to be in abundance

Kuboyama showed concern: that area was notorious for its storms, and the ship was not exactly designed to deal with violent ocean waves. Yamamoto, the chief mechanic, also expressed his reservations, mentioning possible engine problems. But the order was clear. And the sea would not wait.

Fishing and discontent

On February 7, the first fishing operations began. The sailors were hard at work, spending thirteen consecutive hours setting more than 1,500 hooks, arranged on a line about fifty kilometers long. It was like a deadly spider web, suspended sixty meters below the surface, with marker buoys every three hundred meters.

And the result? Only fifteen tuna. A real disappointment. So, on board, the first tensions began to be felt. There were whispers that other fishing boats were returning loaded from the Marshall Islands area. They then decided to move further south to that area. No one realized that they were unknowingly approaching the danger zone of the most powerful nuclear test ever conducted by the United States up to that time.

Castle Bravo: the secret test

Project Castle Bravo marked the beginning of a new era in nuclear weaponry. The United States planned to test a thermonuclear hydrogen bomb, far more powerful than those dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima. The detonation was scheduled for the morning of March 1, 1954, on Bikini Atoll, about 240 km east of Rongelap Island, one of many coral rings in the Marshall Islands.

And the estimated power? 6 megatons. But due to miscalculations and the unpredictable behavior of lithium-7 nuclear fuel, the bomb exploded with a force of 15 megatons-more than 1,000 times that of Hiroshima.

American scientists underestimated the magnitude of the explosion. The safety zone was set at too narrow a radius. Thus, when the Daigo Fukuryū Maru was about 130-140 km east of Bikini, it was hit hard by the radioactive cloud.

The explosion and contamination

On that morning of March 1, 1954, as the Daigo Fukuryū Maru rested adrift with her engine off, the sky above Bikini Atoll lit up with an unnatural and terrifying light. The hydrogen bomb, called “Shrimp” in the coded language of Project Castle Bravo, exploded with unprecedented power.

The shockwave came after seven minutes, violently shaking the small ship and its crew. But even more deadly was the cloud that formed soon after, invisible but deadly.

A shower of white flakes began to fall from the sky, a radioactive ash made of coral dust and condensed nuclear materials. This silent snow slowly settled on the ship, on the skin and clothes of the fishermen, penetrating everywhere.

Kuboyama and the others picked up this dust, some without realizing the danger, others with slight discomfort in their eyes and noses. That substance stuck to their skin, penetrated their lungs and contaminated the entire boat.

Most of the fishermen tried to clean themselves up as much as possible, but the radioactivity was invisible and persistent. Kuboyama, with a presence of mind that reflected his radio experience, collected a sample of that ash in a sheet of paper. He placed it under the pillow where he slept, unaware that he was carrying with him a source of slow death.

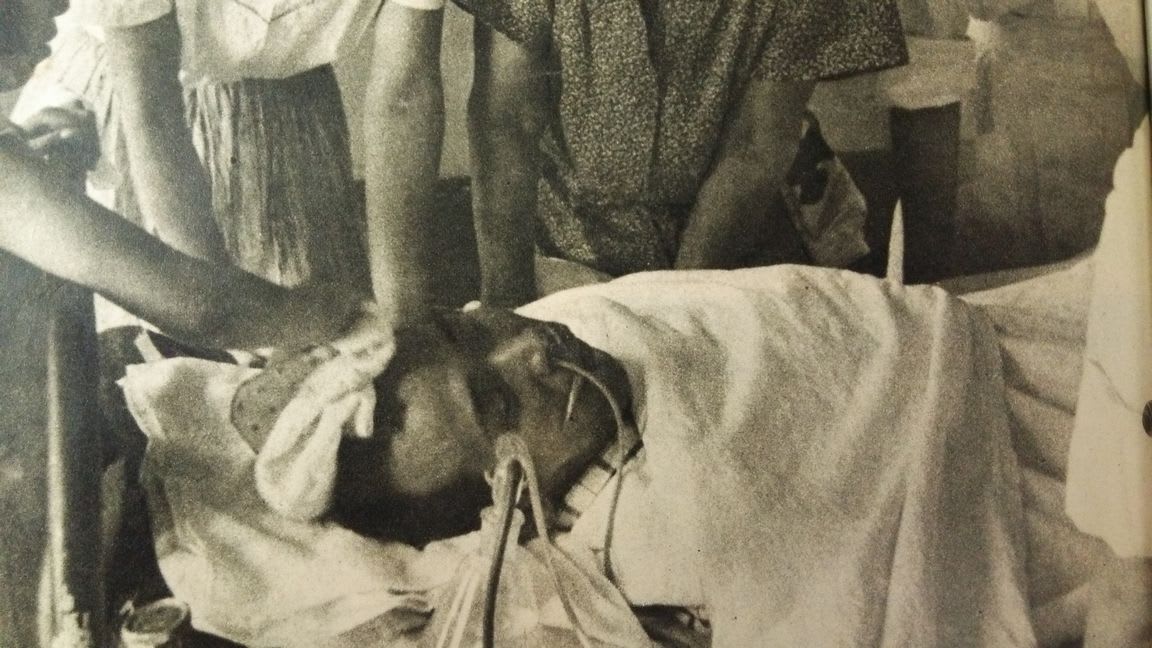

Over the next few days, as the Daigo Fukuryū Maru slowly made its way back to Japan, the first signs of tragedy began to appear on board. Persistent itching, skin irritations, nausea and loss of appetite affected more and more sailors. Some complained of weakness, constant tearing and diarrhea.

The situation worsened rapidly and frighteningly: hair began to fall out in strands, a symptom infamous from accounts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Kuboyama, aware of the possible link between the symptoms and radiation exposure, wrote a detailed report on the dust and his observations. But the crew was already exhausted, fatigued by a mysterious illness.

Return home and first medical checkups

The Daigo Fukuryū Maru arrived at Yaizu Harbor on March 14, 1954. Kuboyama, now weary from illness, did not immediately want to go to the hospital. He covered his face to hide his blackened and darkened skin, aware of how his appearance might attract unwanted attention.

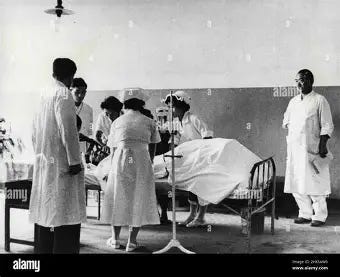

Meanwhile, two sailors were sent to Tokyo for a specialized medical checkup on radiation sickness. Here, with a simple Geiger counter brought close to their heads, a loud ticking sound could be heard: they were radioactive.

Soon, Japanese doctors linked the symptoms to nuclear exposure. The other fishermen were admitted to specialized hospitals in Tokyo and subjected to continuous monitoring. Geiger counters marked abnormal levels, and the gradual decline in white blood cells indicated a picture of severe acute radiation syndrome.

Over the next few days, as the Daigo Fukuryū Maru slowly made its way back to Japan, the first signs of tragedy began to appear on board. Persistent itching, skin irritations, nausea and loss of appetite affected more and more sailors. Some complained of weakness, constant tearing and diarrhea.

The situation worsened rapidly and frighteningly: hair began to fall out in strands, a symptom infamous from the stories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The struggle for life

The following weeks were dramatic. Some sailors developed jaundice and other serious complications. Kuboyama himself alternated between moments of improvement and rapid deterioration. Despite his weakness, he became spokesman for the crew at a press conference on August 5, 1954: a courageous testimony before a nation still unaware of the extent of the disaster.

But his body slowly gave way. On September 20, he said in a trembling voice, "I feel as if my body is being burned by electricity. As if I were crossed by a high-tension line."

Three days later, on September 23, Aikichi Kuboyama died. He was the first recognized Japanese victim of radiation contamination from a nuclear experiment.

Social and diplomatic reactions

News of Kuboyama's death spread quickly. Hundreds of people gathered in front of the hospital, many with eyes full of tears and indignation. Radio and television stopped broadcasting to announce the marcher's demise.

The U.S. government, aware of the seriousness of the situation, sent a letter of condolence to Kuboyama's widow, accompanied by a check for one million yen, a considerable sum at the time, but insufficient to assuage the grief.

Kuboyama's body was cremated and his ashes were preserved in a marble urn placed on the mountain near his hometown of Yaizu. Two hundred students chanted “A Bomb Without Forgiveness,” while some 20 white doves flew in the sky, symbolizing peace and memory.

Historical impact

The Daigo Fukuryū Maru incident marked a turning point in the public perception of nuclear war. It was no longer just a distant and abstract threat, but a tangible and close reality with devastating human consequences.

The case of Kuboyama and his comrades highlighted the need to regulate nuclear testing and to protect civilian populations and innocent fishermen, the unwitting victims of empires' wars.

completely unexpected 'story', a tour de force, dreamlike in its shifts, wide-ranging and deeply felt. My full review should be complete this weekend.

Well done.

Never heard of this particular tragedy. Only the story of what happened to the people on the atoll islands themselves. Still, interesting and sad.